I ordered this book on Amazon, after seeing its name appear on the 1001 Books To Read Before You Die list. Initially, I thought the book was slow-paced, and the lead characters came across as fairly unattractive. There's the unnamed narrator, and The Germanist - a woman who the narrator is attracted to, and within the first couple of pages, she asks him out.

Both of them are doing their research projects in Cambridge. While The Germanist is intense and passionate, the narrator comes across as a lot more relaxed and easy-going. He's desperate to please The Germanist, and the story actually begins when he commits to something only to please her.

I ordered this book on Amazon, after seeing its name appear on the 1001 Books To Read Before You Die list. Initially, I thought the book was slow-paced, and the lead characters came across as fairly unattractive. There's the unnamed narrator, and The Germanist - a woman who the narrator is attracted to, and within the first couple of pages, she asks him out.

Both of them are doing their research projects in Cambridge. While The Germanist is intense and passionate, the narrator comes across as a lot more relaxed and easy-going. He's desperate to please The Germanist, and the story actually begins when he commits to something only to please her.

His research subject is the brilliant albeit eccentric (read schizophrenic) writer, Paul Michel. However, his project focuses on the fiction of the writer, and not the controversial homosexual writer himself. Consequently, he's distant enough from the writer, to not know or care much about the writer and his personal life. The Germanist, on the other hand, is the other extreme. She also knows where Paul Michel has been for the last decade or so - a psychiatric hospital in Paris - and she expects the narrator to go there, and save Michel.

Up to this point, I really didn't enjoy the book. The narrator lacked backbone. On the other hand, The Germanist was incessantly perceptive, passionate and intense. As the narrator's flatmate said:

You can't like women like that. Liking is too negligible an emotion. Anyway, she she scares me shitless.

However, when the narrator reaches Paris, and hits the library, the story picks up pace, and transforms into a page-turner of sorts. He stumbles on some letters written by Michel to Foucault, and familiarizes himself with the author whose works he had gotten to know so intimately. At this point, the central theme of the book unfolds: exploring the mutual love shared between reader and writer, that is never explicitly mentioned to each other.

The final letter that the narrator reads speaks to him, as he realizes that these letters have never been posted, nor read, by the intended recipient, Michel Foucault:

Sex is a brief gesture, I fling away my body with my money and fear. It is the sharp sensation which fills the empty space before I can go in search of you again. I repent nothing but the frustration of being unable to reach you. You are the glove that I find on the floor, the daily challenge that I take up. You are the reader for whom I write. You have never asked me who I have loved the most. You know already and that is why you never asked. I have always loved you.

Foucault seems to be Michel's muse. Their writings explore similar themes and opinions, both reflecting the other's deeply. Neither of them interacted with each other, but they communicated via their published works. Foucault's death in 1984 probably pushed Michel over the edge, and resulted in his admission to a facility in Paris.

Once the narrator discovers that Paul Michel had left the institution in Paris, and is now in one in Clermont-Ferrand, he heads there to find the author, for reasons he did not understand. The initial meeting between the narrator and Michel ends abruptly, but the subsequent meetings (initiated by Paul Michel) leads to a warm friendship and love. The narrator is fascinated and endeared to the wild boy of his generation, and Michel, in turn, grows quite fond of the naive twenty-two year old, referring to him as 'petit', for most of the time they spend together.

As the book progresses, there are some moments that are funny, some that are sad, and some that will stay in your mind forever, just as they did in the narrator's. As a young child once told Paul Michel:

If you love someone, you know where they are and what has happened to them. And you put yourself at risk to save them if you can.

And that's exactly what the narrator set out to do, on being convinced by the formidable Germanist.

This is not an academic book. It's not a book on the life and times of Paul Michel. It's a book about a fascinating character, who's funny, quick-witted spontaneous and humorous. Someone capable of great love, great sentimentality and great generosity. Someone whose world revolves around one person - a reader of his work - and someone who dedicates his life to making his reader proud. The character of Paul Michel is so colorful, that, for what it's worth, he could as easily be a fictional character.

All in all, I'd say this was a 6.5 on 10, most of the points being docked for the first part of the book making me want to put it down, and never ever pick it up again. On the other hand, I'm glad I finished the book, and now, I'm tempted to find some of the works by Paul Michel and Michel Foucault - the two lovers, who never explicitly expressed their love for each other, but still held on to a love that could not be tarnished. Not even with time.

I'm trying to read all the Booker winners, in the next couple of years. This painstakingly dull book, filled with unengaging characters and a pointless plot adds a serious blemish to my plan at the very outset. I struggled through the first thirty pages, and struggled some more 'til I hit page 89, in a week... And then... then I just gave up, and figured this book is not for me. I mean, what a gigantic waste of my reading time!

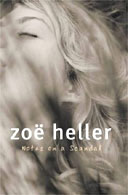

I'm trying to read all the Booker winners, in the next couple of years. This painstakingly dull book, filled with unengaging characters and a pointless plot adds a serious blemish to my plan at the very outset. I struggled through the first thirty pages, and struggled some more 'til I hit page 89, in a week... And then... then I just gave up, and figured this book is not for me. I mean, what a gigantic waste of my reading time!  Who doesn't love a good juicy scandal? The type that makes its way to the tabloids, and has everyone talking about it, and judging the protagonists of the impropriety. Everyone has an opinion, and more oft' than not, it's judging the miscreants. Society. Business as usual.

Who doesn't love a good juicy scandal? The type that makes its way to the tabloids, and has everyone talking about it, and judging the protagonists of the impropriety. Everyone has an opinion, and more oft' than not, it's judging the miscreants. Society. Business as usual.  I ordered this book on Amazon, after seeing its name appear on the

I ordered this book on Amazon, after seeing its name appear on the  This is The Great Gatsby set in the 21st century, in Pakistan. The similarities between the two books are striking, and the endings are almost identical. In fact, I'll go out on a limb and say that this book was inspired by Fitzgerald's classic.

This is The Great Gatsby set in the 21st century, in Pakistan. The similarities between the two books are striking, and the endings are almost identical. In fact, I'll go out on a limb and say that this book was inspired by Fitzgerald's classic. Glitz. Glamour. A love that has survived the War. Extra-marital affairs. Grand parties. Opulence. Alcohol. A yellow Rolls Royce. Chauffeurs. Friendship... and New York in the 1920s (the 'Jazz' age). This pretty much sums up 'The Great Gatsby' - a classic piece of literature from the 20th century.

Glitz. Glamour. A love that has survived the War. Extra-marital affairs. Grand parties. Opulence. Alcohol. A yellow Rolls Royce. Chauffeurs. Friendship... and New York in the 1920s (the 'Jazz' age). This pretty much sums up 'The Great Gatsby' - a classic piece of literature from the 20th century. Pamuk’s The White Castle won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2006, and after reading this book, it is not difficult to figure out why. The Turkish author offers immense insight into the life, philosophies and the psychology of the Hoja (master or teacher) and his slave - a young Italian intellect who was captured by the pirates, and auctioned on the Istanbul slave market. in the 17th century.

Pamuk’s The White Castle won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2006, and after reading this book, it is not difficult to figure out why. The Turkish author offers immense insight into the life, philosophies and the psychology of the Hoja (master or teacher) and his slave - a young Italian intellect who was captured by the pirates, and auctioned on the Istanbul slave market. in the 17th century. This book is not in the same league as A Fine Balance, or even, for that matter, Family Matters. However, the more I think about this book, the more I appreciate it. Mistry has this amazing knack of bringing to life a realistic Indian society, and how they handle various crises and catastrophes that life brings in its wake.

This book is not in the same league as A Fine Balance, or even, for that matter, Family Matters. However, the more I think about this book, the more I appreciate it. Mistry has this amazing knack of bringing to life a realistic Indian society, and how they handle various crises and catastrophes that life brings in its wake. I bought this book very hesitantly. I’m wary of bestsellers, and the way everyone was bigging this up, I was sure this would be a repeat of The Da Vinci Code or The Kite Runner - two books everyone I know loved, but I could barely get through them. For once, I was pleasantly surprised.

I bought this book very hesitantly. I’m wary of bestsellers, and the way everyone was bigging this up, I was sure this would be a repeat of The Da Vinci Code or The Kite Runner - two books everyone I know loved, but I could barely get through them. For once, I was pleasantly surprised.